Zao Volcano

1: Introduction - 2: Overview of geology for Zao Volcano and surrounding area

3: Topography of Zao Volcano

4: Eruptive history of Zao Volcano

5: Eruptions during historic times

6: Petrological characteristics of rocks of Zao Volcano - 7: Recent conditions - 8: Observation system for volcanic activities

9: Notes on volcanic hazard in the future

Acknowledgements / Reference

![]() PREV

PREV ![]() NEXT

NEXT

5: Eruptions during historic times

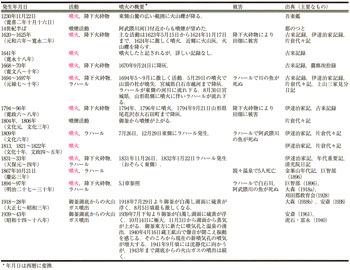

Many historical accounts of volcanic eruptions are available for Zao Volcano, even when considering only well-known events ( ![]() Table 1). The oldest eruption known is the 1230 eruption recorded in Azumakagami. The records indicate that lapilli fell in wide areas to the east, although no further details are given. No records of subsequent of eruptions accompanied by ash fall exist until the 17th century. However, it is noted in a travel record (Miyako no Tsuto) that in the 14th century, active plume events occurred. Therefore, it is difficult to believe that no eruptions occurred during the 14th to 16th centuries even though no records of such activity are available. Since the Edo Period in the 17th century, numerous eruptions were recorded until the 19th century. All of these volcanic activities are assumed to be associated with the present-day Okama crater lake. The newest eruption record is that of 1894–1897; however, during 1918–1928 and 1939–1943, Okama became turbid owing to degassing from the base, and the surface of the lake was covered by sulfur. In both cases, release of volcanic gas and steam from the lake surface was observed; however, the highest water temperature at the lake surface was only about 25 °C. In April 1940, degassing intensified to the east of Okama area, and a new fumarole was formed.

Table 1). The oldest eruption known is the 1230 eruption recorded in Azumakagami. The records indicate that lapilli fell in wide areas to the east, although no further details are given. No records of subsequent of eruptions accompanied by ash fall exist until the 17th century. However, it is noted in a travel record (Miyako no Tsuto) that in the 14th century, active plume events occurred. Therefore, it is difficult to believe that no eruptions occurred during the 14th to 16th centuries even though no records of such activity are available. Since the Edo Period in the 17th century, numerous eruptions were recorded until the 19th century. All of these volcanic activities are assumed to be associated with the present-day Okama crater lake. The newest eruption record is that of 1894–1897; however, during 1918–1928 and 1939–1943, Okama became turbid owing to degassing from the base, and the surface of the lake was covered by sulfur. In both cases, release of volcanic gas and steam from the lake surface was observed; however, the highest water temperature at the lake surface was only about 25 °C. In April 1940, degassing intensified to the east of Okama area, and a new fumarole was formed.

5.1 1894–1897 eruption

For the 1894–1897 eruption, of which a detailed record known as the Meiji eruption exists, here we discuss in detail the eruption records from Kochibe (1896), Omori (1918a), and the official Gazette at that time in addition to the geological examination of Miura et al. (2012). This series of activities intensified during February and September of 1895. The associated ash fall and overflow of Okama crater lake caused flooding, and pyroclastic surges and fall of massive volcanic blocks occurred near the crater.

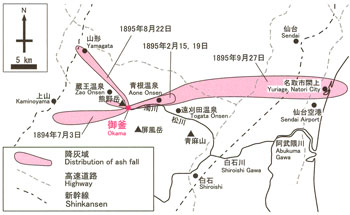

No record is available for the period after October 21, 1867, and immediately before the beginning of the Meiji eruption, no degassing or plume activity from Okama was recorded. In February and March 1894, a plume was observed from Okama, the amount of which increased from that observed in July. The first eruption occurred on July 3, 1894, and a small amount of ash fell with rain on the western foothill. From late July to October, ejection of hot water from Okama occurred, which slowed at the end of October. The first activity peaked around 9 a.m. on February 15, 1895, and the eruption occurred around 8:30 a.m. on February 19. In all eruptions, immediately after the eruption column developed, a lahar flowed down Nigorikawa on the east side. Flooding of the downstream basin reached the Shiraishigawa and Abukumagawa rivers. The lahar developed because the lake water of Okama spilled over as a result of the eruption. The eruption was larger on February 19. Compared with that on February 15, the size of the eruption column was dozens of times larger, and the increased water level due to flooding was several times larger than that of 3 m in Nigorikawa and 120 cm in the Shiraishigawa and Abukumagawa rivers on February15. Ash fall was confirmed at the Aone Hot Spring located approximately 8.5 km east–northeast of Okama on both days ( ![]() Figure 6). On February 19, aggregated volcanic ash of 1–2 cm in diameter was observed. Subsequently, on March 20, a rumbling was noted, which was most likely an eruption, and on March 22, a lahar was observed at the same time as an eruption. On August 22, ash fall as far as Yamagata city was observed. Based on the analysis of the deposit, during the eruption of August 22, a small-scale pyroclastic surge flowed down the area of Okama inside the Umanose Caldera (Miura et al., 2012). The second peak of activities was an eruption occurring around 6 a.m. on September 27, 1895, from which ash fall reached the coast of the Pacific Ocean to the east (Yuriage, Natori City;

Figure 6). On February 19, aggregated volcanic ash of 1–2 cm in diameter was observed. Subsequently, on March 20, a rumbling was noted, which was most likely an eruption, and on March 22, a lahar was observed at the same time as an eruption. On August 22, ash fall as far as Yamagata city was observed. Based on the analysis of the deposit, during the eruption of August 22, a small-scale pyroclastic surge flowed down the area of Okama inside the Umanose Caldera (Miura et al., 2012). The second peak of activities was an eruption occurring around 6 a.m. on September 27, 1895, from which ash fall reached the coast of the Pacific Ocean to the east (Yuriage, Natori City; ![]() Figure 6). This activity caused a lahar that increased the level of the Nigorikawa River by 9 m. Around 6:30 p.m. on September 27, and around 6 p.m. on September 28, small amounts of ash fall, were observed, and the activity appeared to have quieted. The Katta District Education Council (1928) recorded eruptions on March 8 and September 1, 1896. Because no records of activity since the rumbling and plume on January 14, 1897, are available, the details are unknown.

Figure 6). This activity caused a lahar that increased the level of the Nigorikawa River by 9 m. Around 6:30 p.m. on September 27, and around 6 p.m. on September 28, small amounts of ash fall, were observed, and the activity appeared to have quieted. The Katta District Education Council (1928) recorded eruptions on March 8 and September 1, 1896. Because no records of activity since the rumbling and plume on January 14, 1897, are available, the details are unknown.

The eruption had been considered to be phreatic eruptions because the eruption products consist of clays and altered tephra (Miura et al. 2012). However, the product was hot enough to burn vegetation (Kochibe, 1896) and unaltered bombs that underwent plastic deformation were observed (Ban, 2013). Therefore, this series of eruptions is considered to be phreatomagmatic eruption. The total volume of the series of eruptions is estimated to be 6.4 × 108 kg; 6.2 × 108 kg is from the eruption between September 27 and 28, 1895 (Miura et al. 2012). Thus, the most intense eruption of this series had a VEI of only about 1.

5.2 Duration and cycles of eruptions during historic times

The characteristics of eruptions since the Edo Period, for which relatively detailed records are available, are summarized in this section. Eruptive activities during historic time began with small-scale eruptions of ash fall on foothills that lasted for several months to several years along with spillage of the crater lake ( ![]() Table 1). In addition, these eruptive activities repeated the active stage and quiescent period in cycles of about 100 year. That is, two active periods were noted. The first is the 17th century, including eruptions in 1620–25, 1641, 1668 (–70?), and 1694, and the second is the 18th–19th centuries, including those in 1794–96, 1809, 1831–33, 1867, and 1894–97 eruptions. A quiescent period was observed between the 18th and 20th centuries. Furthermore, the active stage can be divided into activities ranging from several days to several years in addition to dormant periods. This fluctuation has been repeated over the years.

Table 1). In addition, these eruptive activities repeated the active stage and quiescent period in cycles of about 100 year. That is, two active periods were noted. The first is the 17th century, including eruptions in 1620–25, 1641, 1668 (–70?), and 1694, and the second is the 18th–19th centuries, including those in 1794–96, 1809, 1831–33, 1867, and 1894–97 eruptions. A quiescent period was observed between the 18th and 20th centuries. Furthermore, the active stage can be divided into activities ranging from several days to several years in addition to dormant periods. This fluctuation has been repeated over the years.

5.3 Scale and style of eruptions in historic times

Excluding the 1230 and 1624 eruptions, the records of individual eruptions do not include pyroclastic fall larger than the lapilli size on the foot of the volcano. Specifically, in eruptions since the Edo Period with detailed records, no wide range of ash fall was noted. Therefore, the scale of individual eruptions was likely not so large. However, the records indicate that the shrine at the summit and vegetation were burned on the 1694 and 1885 eruptions, also the Stage VI product is composed mostly of scoria lapilli–volcanic sand, and volcanic bombs were found near the vent (Ban, 2013); therefore, the eruptions were associated with high-temperature essential materials. In addition, eruptions in 1809, 1831–32, 1867, and 1894–97, caused lahars with acidic water. Records indicate damage to farm fields and human life along with flooding of rivers in the foothills. According to these records, the eruption styles since the Edo Period are characterized by small phreatomagmatic eruptions from the crater lake that caused the lake to spill, resulting in lahars (Oikawa and Ban, 2013). The name “Okama” has been used since the 1694 eruption, and in the 1625 activity, the present-day Okama area was referred to “Haizukamori forest”. That is, the crater lake currently known as Okama did not exist prior to the 1625 eruption. Since 1694, lahars have occurred from the area near the crater at the summit during each eruption; formation of Okama likely occurred during 1625–1694 or later.